Since 2012 is an election year, we thought it fitting to revisit an election year in Koreshan history. The year was 1906 which became, in some ways, a turning point for the Koreshans.

In his 1978 article in Florida Historical Quarterly, Elliott Mackle wrote:

The removal of Unity headquarters to Estero was in fact a consolidation. Furniture and personal goods of Chicago Koreshans were brought south in carload lots. Printing presses used for the production of tracts and magazines were installed in a print shop near the river and publication resumed. 11 The population

grew to about 200, a peak never significantly surpassed during Dr. Teed’s lifetime. Meanwhile, however, the Koreshans’ relations with nearby property owners, which had been relatively free of friction since 1894, began to change. Neighboring small farmers, alarmed at the influx of people into a sparsely populated district, began to speak out against Koreshan plans to build railroads and elevated boulevards through their fields. As a precaution against interference, therefore, Dr. Teed decided upon municipal incorporation of Estero. A meeting of registered voters and affected property owners was held on September 1, 1904. Incorporation was approved, municipal organization and ordinances voted, and officers, all of them Koreshans, were elected. The town’s corporate limits conformed to plans for New Jerusalem:

110 square miles were contained within Estero’s boundaries. The property of several non-Koreshans who objected to incorporation was not included within municipal limits.

Resistance and opposition to the incorporation from the local press were minimal since, in 1904, the Koreshans had supported the election of Philip Isaacs, editor of the Fort Myers Press, forerunner of today’s Fort Myers News-Press.

Mackle goes on to say:

Dr. Teed’s relations with the press had not been very amicable. Reporters had portrayed him as a pompous schemer and a fraud. Teed often had turned such insults to good account by using them as excuses for playing the martyr in the pages of his own publications. Lee County, however, had now become his base of operations and the home of the Unity. Posturing was easily detected, and laughed at, in a small community like Fort Myers. Prudence was required; he wanted good publicity, and he also wanted treaties, however temporary, with the powerful.

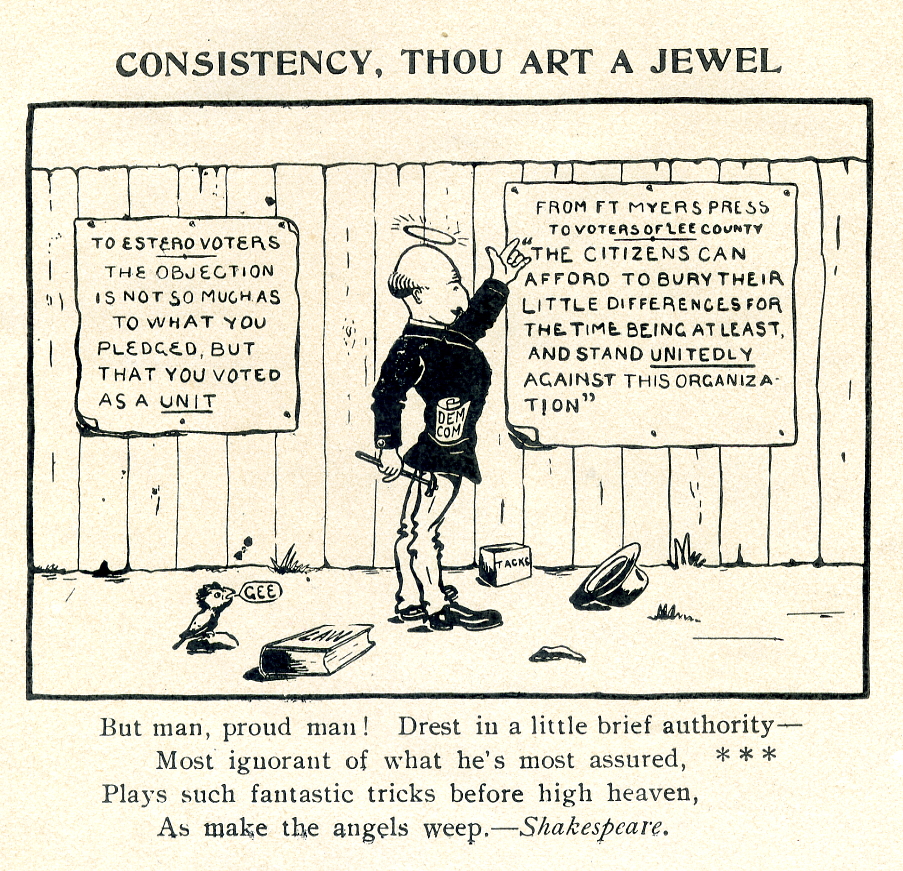

Isaacs’s role as editor, coupled with his elevation from town councilman, his last official position, to the bench, must have made him seem an influential person. In fact he was controlled, as were both the Democratic party organization and the newspaper, by the wealthy Hendry family. The treaty between Teed and Isaacs lasted two years. Teed brought disaster on himself, and on Isaacs, by neglecting to form some new arrangement. And Isaacs, like Teed, misjudged the power of his position, thereby contributing to his own undoing. These personal disasters, which accompanied a severing of public ties between Estero and Fort Myers, were occasioned by the events of the election of 1906. The seeds of the conflict had been sown two years earlier. Municipal incorporation had entitled Dr. Teed and his officials to claim a share of county road tax funds, but they found that county officers were loath to divert dollars from their own projects, particularly those in Fort Myers. There was also, in some quarters, a resentment against the northern newcomers who sought to establish what might become a rival county seat, who boasted that they would revolutionize the world and turn it inside out, and who followed a messiah other than Christ. County officials, needing a bargaining chip, looked back to the records of the Democratic primary election of May 1904, when Koreshans had been permitted to register and to vote. 15 In the November general election, however, the Koreshans had voted for Republican Theodore Roosevelt, rather than the Democrats’ nominee. Although the Koreshans had otherwise supported the ticket, this defection provided an excuse to disenfranchise them for the election of 1906. The instrument of this disenfranchisement was a pledge which participants in the first Democratic primary of May 1906 were required to sign if challenged. It stated that the voter would support all Democratic nominees of 1906, and that he had “supported the Democratic nominees of 1904, both state, county, and national.“ Based upon laws passed to deny blacks the franchise, this pledge was so worded as to exclude those who had voted for Roosevelt and those who had not been in Lee County in 1904 and had therefore not voted. The Koreshans stubbornly refused to be intimidated. They appeared at the Estero precinct polling station on the day of the first Democratic primary, protested against the pledge, but then signed it after crossing out certain of the qualifications, and bloc-voted for the candidates of their choice. The Democratic executive committee, of which Philip Isaacs was chairman, thereupon threw out the entire vote of the Estero precinct, including eight votes by the non-Koreshan electors, and instructed election inspectors to bar Koreshans from voting in the second primary. Isaacs and the party had not found it necessary to curry Dr. Teed’s favor. The Democratic candidates for county office could be elected without Estero support, and the Koreshans were ineligible to participate in Fort Myers municipal contests-a bond referendum, an election for town aldermen, in which Isaacs was a candidate, and the elevation of a Hendry to the office of mayor.

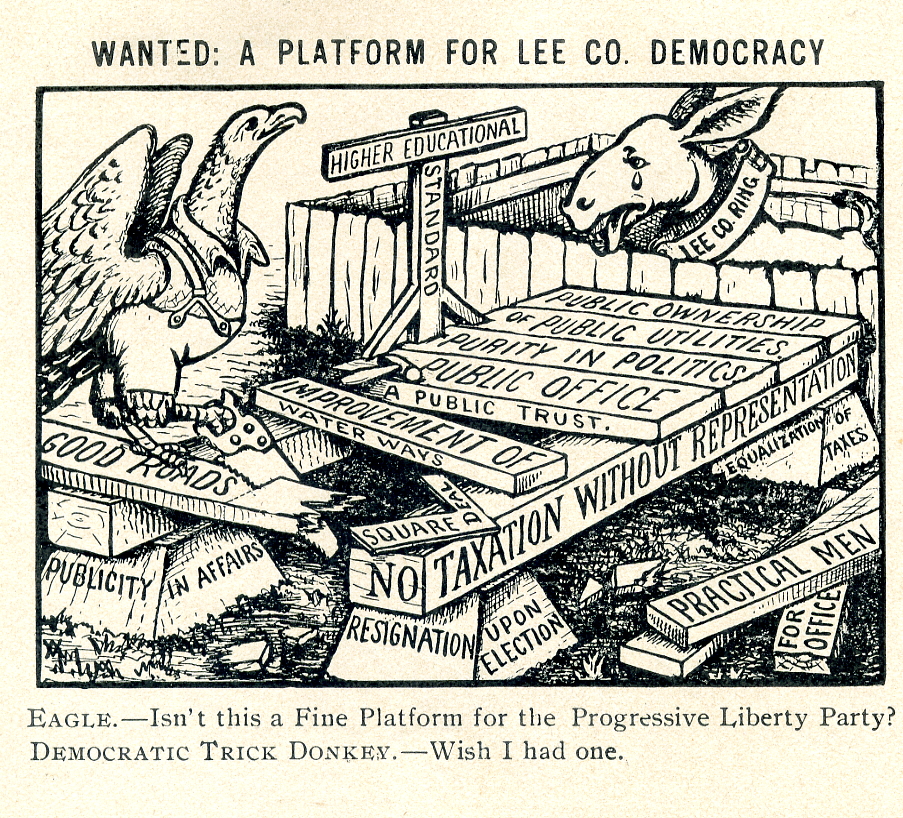

When the Koreshans began publication of the “American Eagle”, its main purpose, as stated last month was to oppose Issacs and others in the 1906 election.

Here are some examples of the political “cartoons” that the Koreshans created. These are contained in a little booklet given to Dr. Teed by Walter Bartsch, a member of the Unity. You can view the entire booklet of cartoons by going to this link